If you were to transcribe a standard, polite conversation between two men in downtown Tehran and hand it to a psychiatrist in New York, he would immediately call the suicide hotline.

“I will sacrifice myself for you.”

“No, I will die for you first.”

“I want to circle your grave.”

“I want to eat your liver.”

“May I be the dirt under your feet.”

This isn’t a goth poetry slam. This is two guys deciding who walks through a door first.

I live in Italy now. Italians are famous for being expressive, right? They talk with their hands, they shout, they love life. But Italian politeness is sane. If an Italian barista gives me a coffee in Milan, I say Grazie mille. He smiles, I smile, we move on. It is a transaction. It is sane.

In Iran? If I treated a favor with that much lightness, I would be considered a barbarian.

In Farsi, we don’t just “appreciate” people. We offer to slaughter ourselves for their amusement ritually. We offer to become a human shield against their bad luck. We utilize a linguistic toolkit that Western linguists call “Self-Abnegation Politeness Strategies,” but which I call Emotional Necrophilia.

If you are Learning Persian, you have probably memorized the textbook words for “Thank you” (Mersi or Mamnoon). But if you want to understand the soul of the country—and if you want to date an Iranian without accidentally offending them—you need to understand why we are so obsessed with death.

Let’s dissect the Ghorbanat Paradox and the dark art of Persian politeness.

The Anthropology of “The Sacrifice” (Why We Are So Morbid)

To understand why I tell my mother “I will die for you” when she passes me the salt, we have to put on our Political Analyst hats for a second.

The root word you will hear 50 times a day in Iran is Ghorban (قربان). It comes from the Semitic root Q-R-B, meaning “to draw near” (to God).

In ancient times—we’re talking pre-Islamic and early Islamic history—you didn’t just say “thanks.” You proved your loyalty through sacrifice. You slaughtered a sheep, a camel, or a goat to show devotion to a deity or a King. Blood was the currency of loyalty.

Fast forward a few thousand years. We stopped killing camels at every dinner party (it’s bad for the carpet), but the psychology of debt remained.

The Zero-Sum Status Game

In a high-hierarchy society like Iran, status is a zero-sum game. For me to raise your status, I must lower mine.

I cannot just say “You are great.” That’s cheap. I must say “You are a King, which implies I am a peasant, and therefore my life is disposable compared to yours.”

It sounds intense, I know. But in 2025, this has lost its literal blood-soaked meaning and become a verbal tic. It is the social lubricant of Iranian society. It is how we acknowledge hierarchy so we can ignore it and be friends.

The Glossary of Doom: A User’s Guide to Persian Death Wishes

Okay, let’s get into the street slang. You need to know these, but you also need to know when to use them. If you use them wrong, you look like a psychopath.

1. Ghorbanet Beram (The Swiss Army Knife)

Fingilish: Ghorbanet beram

Script: قربانت بروم

Literal Translation: “May I go and become your sacrifice.

” Actual Meaning: “Thank you,” “Goodbye,” “I love you,” “Okay.”

This is the most common phrase in the Persian language after Salam.

- Scenario: You buy cigarettes. The shopkeeper gives you change.

- You say: Ghorbanet. (Thanks, boss).

- Scenario: You are hanging up the phone with your aunt.

- You say: Ghorbanet, Khodahafez. (Die for you, bye).

It is so common that it has lost its weight. It’s like the American “I’m dead” (meaning: that’s funny). But be careful: it is informal. Do not say this to a government official, a professor, or a police officer unless you want a very confusing interrogation.

2. Doret Begardam (The Orbital Mechanics of Love)

Fingilish: Doret begardam Script: دورت بگردم

Literal Translation: “Let me circle around you.”

Actual Meaning: “You are adorable,” “I cherish you.”

This is the one that confuses my Italian friends the most. “El, why are you circling people? Are you a shark? Are you a satellite?”

Think about the Kaaba in Mecca. Pilgrims circle it (Tawaf) because it is the center of the spiritual universe. Or, think of the Moth and the Flame. In Persian poetry, the moth (Parvaneh) is the ultimate lover because it circles the flame until it gets too close and is incinerated. Sad, but also poetic.

When you tell someone Doret begardam, you are saying:

“You are the center of my orbit, and I am willing to burn up in your atmosphere.”

Usage Rules:

- High Frequency: Grandmothers talking to grandchildren.

- Medium Frequency: Lovers talking to each other.

- Zero Frequency: Two straight men watching football. (Do not do this. It’s weird).

3. Fadat Sham (The Bodyguard)

Fingilish: Fadat sham Script: فدات شم

Literal Translation: “May I be your ransom/sacrifice.”

Actual Meaning: “I appreciate you deeply.”

This is slightly different from Ghorban. Fada implies taking a bullet for someone. It means if Bala (evil/misfortune/calamity) is heading towards you, I am volunteering to jump in front of it so it hits me instead.

This is the bread and butter of Tarof (Persian etiquette). It is a shield you throw up to show humility. If someone compliments your shirt, you don’t say “Thanks.” You say: Male shoma (It is a gift for you, I don’t mean it, but I must offer it), fadat sham.

(Note: You don’t actually have to give them the shirt. But you have to OFFER to give them the shirt, and offer to die. It’s a dance. Just keep up).

4. Marg-e Man? (Weaponized Hospitality)

Fingilish: Marg-e man?

Script: مرگ من؟

Literal Translation: “My death?”

Actual Meaning: “I swear on my life / Do this for me.”

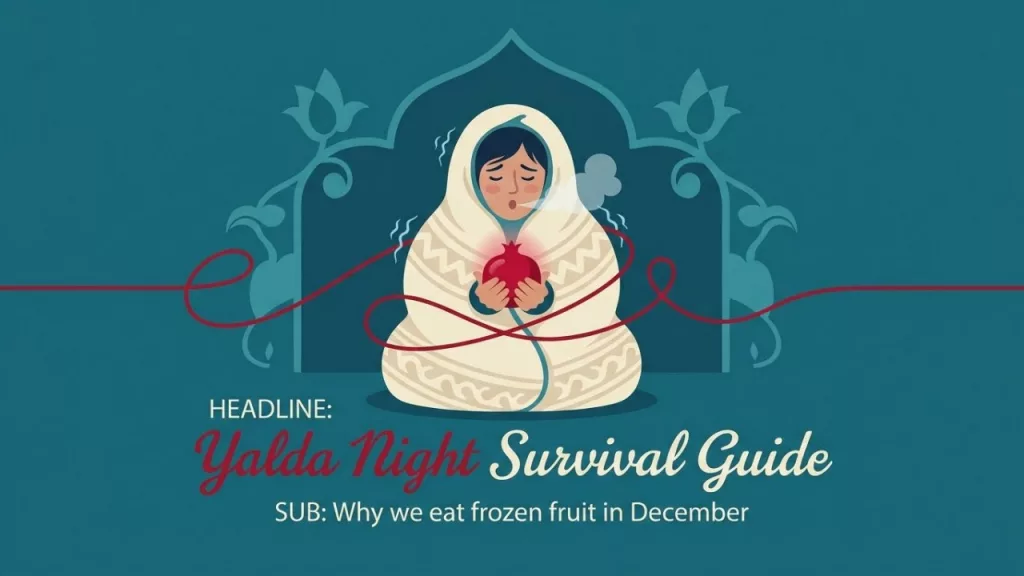

This is not polite affection; this is emotional blackmail. In Italy, if I offer a guest pizza and they say “No, I’m full,” I say “Okay, more for me.” In Iran, that is illegal.

If a guest refuses fruit, tea, or dinner, you must verify if they are lying (Tarof) or actually full. You deploy the nuclear option: “Marg-e Elyar bokhor.” (On Elyars’s death, eat this cucumber).

Now they are trapped. If they don’t eat the cucumber, they are theoretically responsible for my death. It forces them to comply. It is brilliant, manipulative, and essential… but only if you maintain intense eye contact while saying it.

5. Nokaretam / Chakeram (The Bro Code)

Fingilish: Nokaretam / Chakeram

Script: نوکرتم / چاکرم

Literal Translation: “I am your servant / I am your slit-open slave.”

Actual Meaning: “I got you, bro.”

This is exclusively for the boys. This is “Bro-talk.” Chaker comes from an old word meaning someone who has torn their collar open in grief or servitude. When your friend picks you up from the airport, you don’t say “Thanks man.” You say: “Chakeretam dadash.” (I am your slave, brother).

It establishes equality by pretending to be inferior. Paradoxical? Yes. That’s Iran.

Body Horror: Cannibalism and Self-Burials

We’ve covered death. Now let’s cover anatomy. The morbidity of the Persian language extends to our internal organs.

1. Jigar-to Bokhoram (The Hannibal Lecter Twist)

Fingilish: Jigarto bokhoram

Script: جیگرتو بخورم

Literal Translation: “I want to eat your liver.”

Actual Meaning: “You are delicious/adorable/I love you intensely.”

In the West, the Heart is the center of emotion. In Persian anatomy, the Liver (Jigar) is the seat of deep affection and courage (unlike English, where being “livered” usually means you are a coward).

So, naturally, the most romantic thing you can say to someone is that you want to consume their liver. If you say this on a first date in Milan, the Carabinieri will arrest you. If you say this in Tehran, the girl will blush.

It implies that someone is so delicious, so cute, so essential to your existence, that you want to consume them. We also call people Jigar as a noun. “Che Jigarehi.” (What a liver she/he is = What a hottie).

2. Khak Too Saram (The Self-Funeral)

Fingilish: Khak too saram

Script: خاک تو سرم

Literal Translation: “Dust on my head.”

Actual Meaning: “I should die of embarrassment / I messed up.”

When we mess up, we don’t just say “Oops.” We invoke a funeral. This refers to the ancient practice of pouring grave dirt on your head during mourning.

- I dropped my phone? Khak too saram.

- I failed my exam? Khak too saram.

- I forgot your birthday? Khak too saram.

We live our lives constantly oscillating between offering to die for others (Ghorbanet) and mourning our own stupidity (Khak too saram). It is an emotional rollercoaster, I know.

The Political Science of “Simping” (Power Dynamics)

So, why do we do this? Is it just low self-esteem? No. My Political Science professors here in Italy love to talk about “Power Dynamics.”

Iran is a High-Context Culture with a history of absolute monarchy. In such systems, direct language is dangerous. You need layers. You need safety buffers.

When I say Ghorbanet Beram (I will die for you), I am not actually being submissive. I am indebting you. By lowering myself so drastically, I am forcing you to treat me with kindness. It is a Reverse Power Play.

- If I claim to be your servant, you are morally obligated to be a benevolent master.

- If I offer to die for you, you cannot attack me.

It is a way of controlling the interaction by surrendering control. It’s also about Aberoo (Face/Honor). If I don’t use these phrases, I look cold, arrogant, and “dry” (Khoshk). In Iran, being “dry” is a social death sentence. You have to be “warm” (Garm), and warmth requires the vocabulary of sacrifice.

How Not to Embarrass Yourself

Reading this is easy; using it is hard.

If you are a beginner, here is my advice:

- Start with “Ghorbanet.” It’s safe. Use it instead of “Mersi” sometimes.

- Avoid “Jigar” at work. It’s too intimate. You don’t want to eat your boss’s liver. That is an HR violation in any country.

- Don’t overdo it. If you say “I will die for you” to a taxi driver who is ripping you off, you are just a “Simp” (or Zan-Zalil — literally “Woman-Humiliated,” or what you call “Whipped”). You have to maintain your frame.

Persian is not just a language; it is a role-playing game where everyone is trying to out-polite each other until one person collapses.

I’m a PolSci student in Italy, and I spend my days analyzing these cultural codes so you don’t have to learn them the hard way. I don’t just teach you grammar; I teach you how to read the room.

Do you want to learn how to flirt, fight, and negotiate like a real Tehran local?

👇 Book a trial lesson before I die of boredom (Ghorbanet Beram): Start Your Persian Training Here